Overview

1924 Indian Citizenship Act

Authors and Contributors:

Cheryl Tuttle (Yurok/Karuk) Educator and Cultural Preservationist

Formatted and edited Maggie Peters (Yurok/Karuk) NASMC Learning Specialists Humboldt County Office of Education

Grades: 9-12

Suggested Amount of Time: Two 55 minute sessions

Curriculum Themes

- History

- Law/Government

- Cross Curricular Integration

Learning Goals

- Identify the cause for 90% population decline among California Indians.

- Examine citizenship prior to 1924.

- Evaluate the purpose of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

- Understand the connection of WW1 veterans to citizenship rights.

- Analyze the impact of the 1924 Indian Citizenship to voting rights.

Unit Overview

This unit introduces the historical, cultural, and political impacts of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act by examining how U.S. citizenship was extended to Native peoples and the ongoing struggle for sovereignty and civil rights that has followed. Through interactive activities, visual slides, primary source analysis, and student-led research, learners will build an understanding of Native identity, government policy, and resistance through an Indigenous perspective.

The unit is structured into four flexible parts that can be taught across multiple days or as a condensed unit, depending on time and class pacing. The provided Google Slides are animated and essential to guiding instruction. Each slide is thoughtfully sequenced to build knowledge gradually and engage students with images, prompts, and direct content. Slides should be presented in “slideshow mode” for proper animation and pacing.

Part 1 – Setting the Historical Context (60 min):

Students begin by examining how colonization, the California mission system, the Gold Rush, and state-sanctioned violence devastated Native Californian populations and lifeways. An impactful survivor simulation, vocabulary work, and visual activities help students grasp the scale and complexity of this history.

Part 2 – Citizenship, Sovereignty, and Identity (60 min):

This lesson centers Native perspectives on identity, belonging, and sovereignty. Students learn why Native Americans were excluded from the 14th Amendment and explore the legal and personal contradictions of being “granted” citizenship. Primary sources, discussion prompts, and handouts help students unpack the emotional and ethical impact of U.S. policies toward Indigenous peoples.

Part 3 – Mini Research & Group Presentations (60 min):

In small groups, students research and present on one of two focused topics, “The impact of Native American veterans on the 1924 Act” or “Ongoing challenges related to Native citizenship and voting rights.” This activity supports collaboration, critical thinking, and respectful discussion. Group presentations allow for creativity and build public speaking skills, with a simple scorecard included for self- and peer-assessment.

(additional curriculum from PBS The Warrior Tradition can be found in the resources)

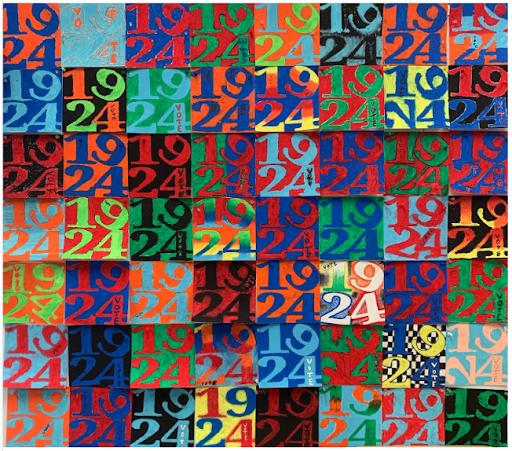

Part 4 – Creative Reflection Through Art (55 min):

The final session invites students to process and reflect through visual expression. Students will contribute to a class mural. This closing activity invites healing, creativity, and will provoke public awareness of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

Teacher Background

Before teaching about the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, it is essential for educators to have a grounding in both the history and the best practices for approaching topics that involve trauma, injustice, and Native American experiences. This history is often painful and rarely taught accurately in schools, yet it is critical to understanding the lives, rights, and resilience of Native peoples today.

By 1924, Native Californians had endured over 150 years of violence and colonization. Beginning with the Spanish mission system in 1769, Native people were forced into religious conversion, hard labor, and cultural suppression. When California became a U.S. state in 1850, these conditions worsened. California’s government actively supported extermination policies, including paying bounties for Native scalps and passing laws like the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, which stripped Native people of basic rights and enabled the indenture and trafficking of Native children and adults. The Gold Rush brought widespread land theft, environmental destruction, and increased settler violence. By 1900’s, the Native population of California had declined by an estimated 90%, devastated by settler colonialism.

Despite this, Native people persisted. Many joined the military during World War I, more per capita than any other ethnic group, often with the promise of citizenship upon their return, forcing Native people to “earn” their citizenship, unlike any other population in the U.S. Their service helped pave the way for the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted U.S. citizenship to Native Americans while allowing them to retain membership in their tribal nations. However, many Native people still faced barriers to full participation in American democracy, including voter suppression tactics like poll taxes, literacy tests, and outright discrimination at the polls. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that those legal obstacles were formally outlawed, though voter suppression continues in modern forms, including limited polling access and rejection of tribal IDs in some states.

As educators, teaching this history requires care, honesty, and cultural responsiveness. Native students, whether they have deep knowledge of their tribal history or not, may carry generational trauma related to these events. It is important to avoid putting Native students on the spot, expecting them to speak on behalf of all Native people, or making them feel like their identity is only tied to loss and pain. All students benefit from learning about Native histories in ways that also center honesty, survival, resistance, community strength, and cultural revitalization.

To support students in this lesson:

Use trauma-informed practices. Let students process in quiet, non-verbal ways if needed.

Always frame Native peoples as sovereign nations with distinct cultures and systems of governance, never depict Native peoples solely as peoples of the past.

Highlight Native resilience alongside historical oppression. Include contemporary voices, examples, and achievements.

Let students know it’s okay to feel uncomfortable—but that facing injustice is part of learning to be a critical thinker and responsible member of society.

You don’t need to be an expert to teach this history, you just need to approach it with humility, honesty, and a willingness to keep learning. Your care and preparation matter. When done with respect, this lesson not only builds historical understanding but also deepens empathy, civic awareness, and cultural respect in the learning environment.

Historical Background:

Prior to 1924, the California Indian had experienced devastating loss of life, culture, and land. When California became a Spanish Territory in 1769, Spain began to occupy California through the mission system and military outposts, many Native people were the brought by force or coercion to the missions as forced labor to build the missions, farm the land, and do the domestic and labor intensive work required for large populations. Native people were required to renounce their tribal beliefs, culture and language and become Christianized and follow the directives of the Catholic Church. This type of colonization primarily occurred along the Pacific coast of California from Mexico to Mendocino County in northern California. As Spain began to occupy the state and divide the land amongst its citizens, California Natives were driven off their land, subjugated and forced to work on the Rancheros or fend for themselves in unpopulated areas.

California was ceded to the United States in 1848 and became a state In 1850. Gold was discovered in 1848 and the state’s population dramatically increased. Hundreds of thousands of people came to California to strike it rich in the gold fields or exploitation of other resources. While the settler population significantly increased, the Native population dramatically decreased. About 90% of the Native Californians died from disease or murder and many tribes were displaced without a home, without a traditional land base and suffering from refugee conditions . The first governor, Peter Burnett, called for a “War of Extermination” of the local natives and empowered the state government to pay vigilante groups to hunt down and kill Natives.

In the meantime, in 1850, California implemented a law called, “The Act for Government and the Protection of Indians” was created which prohibited Natives from defending themselves in court, allowing Natives to be indentured if deemed vagrants or if they were convicted and found guilty in court. It allowed Native children to be placed in “custodianship”, which was another way of indenturing them, this led to children being kidnapped and sold to the highest bidder. This Act also paid vigilante groups for Native scalps

From 1848 to 1855, the forty-niner gold seekers were devastating the land with hydraulic mining, logging large areas, damming the rivers and creeks, all of which allowed sediment to clog up the rivers and affect the fish food source. On land, native animal species were being overly hunted and displaced by range and farm stock. When Natives, who had been displaced from their homes, went back to their traditional areas, they would find their lands occupied and/or devastated from the search for gold and a significant increase in non-native settlers claiming the land.

As a result of the missions, the gold rush and the extermination policies, the California Indian population decreased about 90% before the year 1865. The Natives that still survived, experienced the effects of extreme loss in terms of tribal populations, the eradication of entire villages and tribes, and many surviving Natives were now homeless or fleeing hostilities. .

By the time of 1924, many of the native people had learned how to assimilate into the settler population and many were driven onto reservations, which in many cases, were not within their original homelands. Despite the hostile treatment by settlers, when World War 1 broke out in 1914, many native people joined the effort and fought overseas on behalf of the U. S.. Some were recruited, but many joined on their own accord. The percentage of Native Americans in WW1 exceeded any other ethnic group. Natives who joined were promised citizenship upon their completion of military service. When the Native Americans who served in WW1 returned home, they encouraged and staunchly advocated for all Natives to receive citizenship. While being the first people on the land, Native Americans were granted citizenship after White Americans, Black Americans and women. The Citizenship Act was signed by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2, 1924. The Indian Citizenship Act allowed all natives to become citizens of the United States and retain their right to be members of their Native tribe.

Despite the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, many Native Americans faced legal and systemic barriers to voting. Some states had required literacy tests, which excluded Natives who didn’t speak English but spoke only their Native language. Some states instituted poll taxes, which required an individual to pay a tax to vote. Some voting precincts refused to let a Native person vote because they were already members of their tribe, hence the precinct said they couldn’t be a citizen of their tribe and be considered a citizen of the U. S., although the act explicitly permitted a dual standing. It wasn't until the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which was the result of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s, did all Native people gain the right to vote and all the states had to adhere to dictates of the federal government.

Today, Native people must actively remain vigilant to secure the right to vote. Redistricting, making polling places hundreds of miles away from reservations, or requiring street addresses have been some of the ways to discourage Native voting. However, today, there are many watch groups, such as the Native Americans Rights Fund, that watch current happenings across the nation to make sure states and the federal government are accountable to Native American citizens.