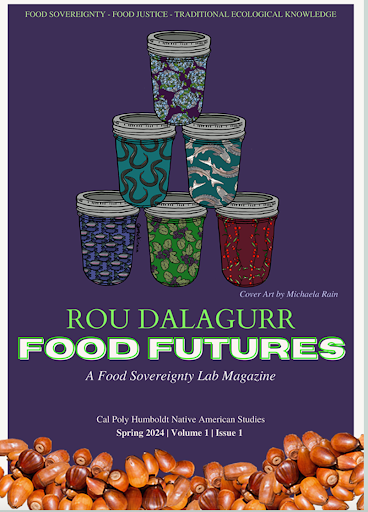

Overview

Indigenous Food Sovereignty and Health

Author: Cutcha Risling Baldy, Ph.D (Yurok, Hupa, Karuk)

Chelsea Rios Gomez, M.A.

Lesson partner: Humboldt County Office of Education

Grades: 9-12

Suggested Amount of Time: 45 minutes

Curriculum Themes

- History

- Cultural Strengths

- Relationship to Place

Learning Goals

Students will define food sovereignty and explain its importance to the health, culture, and sustainability of communities.

Students will identify the cultural, ecological, and nutritional significance of foods like seaweed, acorns, and salmon in Indigenous food systems.

Students will analyze the impact of colonization on Indigenous food systems and recognize the importance of restoring food sovereignty in contemporary contexts.

Lesson Overview

This lesson introduces students to Indigenous food sovereignty and the concept of food futures, emphasizing the importance of traditional food systems in maintaining cultural identity. Through a focus on seaweed, acorns, and salmon, students will explore how these foods are integral to Indigenous cultures, health, and sustainable practices. The lesson also examines the impact of colonization on Indigenous food systems and the ongoing efforts to restore food sovereignty in communities. In this lesson students will explore connections between health of the land and health of the people and apply this to their own understanding of health and wellness.

Teacher Background

Food sovereignty centers on the right of individuals, communities, and nations to control their own food systems. The Declaration of Nyéléni defines food sovereignty as the right to healthy, culturally appropriate food produced through sustainable, ecologically sound methods. It emphasizes the importance of local decision-making and the need to build knowledge and skills in food production, while also highlighting the essential role of Indigenous voices in shaping sustainable food systems. Revitalizing traditional food practices through Indigenous food sovereignty is crucial to reclaiming our food systems and fostering sustainability, both locally and globally.

In Northern California, Native communities maintain deep connections to traditional food sources and ecological practices that have supported a thriving, sustainable food system for thousands of years. These Indigenous food systems, which include practices like cultural burning, promoted ecological abundance while sustaining local ecosystems. Historical accounts often described California’s landscape as a "well-tended garden," shaped by Indigenous ecological knowledge. Despite ongoing efforts to destroy Native food systems through colonization, California tribes have remained resilient, developing movements around key foods such as acorns, salmon and kelp. These food sovereignty efforts not only preserve cultural practices but also respond to contemporary challenges like food insecurity and environmental degradation, providing a foundation for the revitalization of Native foodways.

Colonialism, especially during the Gold Rush and Spanish Mission periods, violently disrupted Native food practices. Spanish settlers banned Native peoples from consuming traditional foods and forced them into agricultural labor under harsh conditions, further eroding food systems. Later, policies such as the Dawes Act and the forced relocation of Native peoples onto reservations exacerbated this disruption, including attempts to eradicate food staples like acorns. The U.S. government also targeted Native food sources as a way to weaken and displace Indigenous populations, like the mass killing of buffalo and the destruction of agricultural fields. Today, the ongoing dispossession of Native lands continues to hinder access to traditional food sources, exacerbating food insecurity in many Indigenous communities. However, Native groups have remained committed to food sovereignty, working to restore traditional knowledge and practices through initiatives like community gardens, food security programs, and educational efforts aimed at rebuilding connections to the land and food systems. These efforts are essential not only for food security but for social and environmental justice.